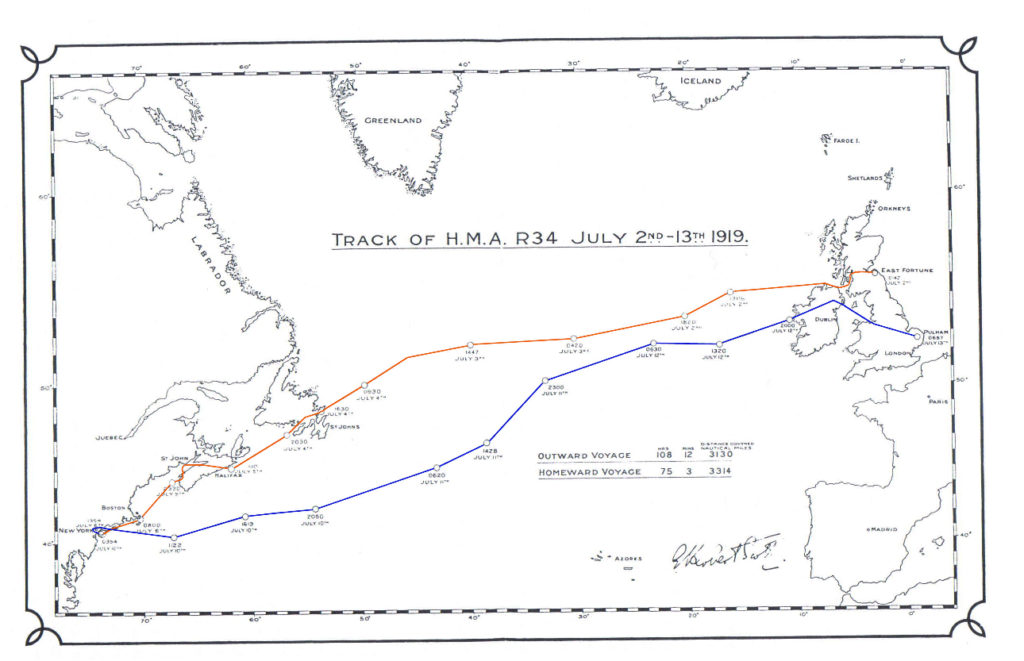

The Route Map of the R-34’s Historic Double Trans-Atlantic Crossing in 1919.

The Orange Line is the Crossing from Scotland to New York and the Blue Line is the crossing from New York to Pulham.

Saturday, July 12, 1919 began beautifully. The weather began clearing and the sea was visible at 2500 feet.

At 5 am, General Maitland recorded: “Magnificent sunrise; the sun slowly appears above the cloud bank ahead of us in a blaze of golden light, and we head straight into it.”

An hour later, the ship is running on three engines only as the after engine is being repaired. The airspeed is 32 knots. Major Scott takes the ship down to 900 feet to sight the water. Ground speed is only 15 knots at that altitude, so he returns to 2800 feet where the ship’s ground speed is 36 knots, or 41 mph (67 kph). The R-34 is approximately 760 miles from her base — and home.

General Maitland wrote, “Breakfast this morning is a festive meal, as we reckon it should be our last breakfast on board, and we are rather lavish in our issues.”

Wives, families, and sweethearts are gathering at East Fortune in Scotland awaiting the ship’s homecoming. But at 10 am, the Air Ministry instructs the R-34 to land at Pulham in Norfolk, England instead. The message is not understood as the weather is better for landing at East Fortune then it is at Pulham.

By noon, the weather has turned very cold and once again the R-34 is fighting a headwind. Everyone realizes they will be breakfasting on board ship tomorrow morning and feel disappointed.

In the evening, the ship runs into two sudden squalls. Maitland notes the ship is very steady. Then at 7:25 pm land is in sight off the starboard bow and at 8 pm the R-34 crosses the coastline a little to the north of Clifden, County Mayo, Ireland. From the coast of Long Island to the coast of Ireland, flight time was 61 hours and 43 minutes.

Above the Hills and Lakes of Ireland

The euphoria is dampened however, when at 11:30 pm the Air Ministry repeats the message to land at Pulham. Major Scott increases altitude to 5000 feet and sets course for Pulham.

No explanation has ever come to light as to why the R-34 was redirected to land at Pulham instead of East Fortune. Especially when the weather, critical for airship safety in landing, was better at the Scottish base.

Patrick Abbott, in his book Airship: The Story Of R-34, gives the following possible explanation:

Those who supported only an aeroplane programme may have contrived the altered destination in order to avoid the publicity of the great welcome that was being planned at East Fortune. Pulham, by contrast, was comparatively isolated… so ensuring the minimum fuss and excitement. If this theory is true—and it accords with later policy development and the shabby treatment soon meted out to everyone on board—then the manoeuvre was an unworthy affront to servicemen who could neither disobey nor complain.

I think Mr Abbot makes a valid point. Given the subsequent history of the British government’s bureaucratic antipathy towards building and maintaining an airship fleet, it seems only logical the R-34 and her crew ended up as victims of bureaucratic politics and cost-cutting excuses.

Britain was in an admirable position to seize the day and exploit the commercial possibilities of the airship. However, as with their American cousins, the British largely saw the airship as a military craft. However World War I had clearly shown the future of the giants was not as a weapon of war, but as a tool of peace. Only Doctor Hugo Eckener of the Zeppelin company realized this and was intent on pursuing the true future of the rigid airship. If he’d had the capital and didn’t have the animosity of the Allies and their wreaking of vengeance on the German people, he would have succeeded.

Stay tuned! Tomorrow the epic voyage comes to an end. Prepare to give the memory of those brave men the recognition they truly deserve. A recognition denied them in their day due to petty politics.

Share This!