The time period between World War I and World War II was the heyday of the rigid airship. Those two decades were filled with the exploits of what the great airships did and the dreams of what the future might hold for air travel.

1919 was an auspicious year. The war to end all wars was over. The airplane had developed in technological leaps and bounds. The airship as well had been refined. And whereas the airplane was mostly still a toy or of use for short distance flights, the airship was viewed as a machine of great commercial and military value.

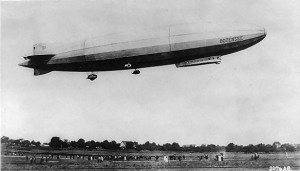

On the 6th of March 1919, the British rigid airship, R33, took its first flight. Eight days later, her sister ship, R34, made it’s inaugural flight. Both airships were based on the design of German zeppelins in 1916. It is interesting to note, these were the most successful of any British rigid airship. The R33’s career lasted for nine years before she was scrapped in 1928 due to severe metal fatigue in her frame.

The R33 near her hanger:

The R34 made the first east to west crossing of the Atlantic by air (the more difficult crossing due to the prevailing westerly winds) in July 1919, flying from England to Canada. Hot meals were even served on board, courtesy of a hotplate welded to an engine exhaust manifold. On the 13th of July 1919, the R34 returned to England; completing the first ever round trip across the Atlantic by air.

The flight of the R34 in 1919 fueled speculation of the possibilities for commercial airship flights across the Atlantic on a grand scale.

August 20, 1919 saw the first flight of the LZ-120, Bodensee, the Zeppelin company’s new commercial airship for the DELAG airline. She flew over 100 flights, carrying 2,322 passengers over 31,000 miles (50,000 km). Unfortunately, the Allied powers forced the Germans to turn over the Bodensee to the Italian government as a war reparations in July 1921. As the Esperia, she made flights for the Italian government, including a 1,500 mile long distance flight, before being scrapped in July 1928.

The Bodensee:

The LZ-121, Nordstern, never served the DELAG and was turned over to France on 13 July 1921 as war reparations. The French Government never made much use of the ship and she was scrapped in 1926.

A substantial book could be written chronicling just the airships of the interwar period. To exemplify The Wonderful Machine Age, I’ll focus on the triumphs and the dreams.

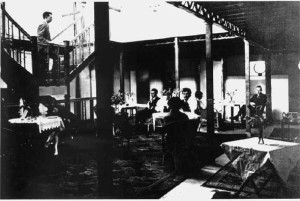

The short two year life of the R100 was a dream come true. The world’s first luxury commercial airship. Her first flight was on 16 December 1929. She and her sister ship, the R101, were, at the time, the largest airships ever built. She was meant to carry 100 passengers in elegance for an envisioned transatlantic passenger service. In 1930, she flew from England to Canada and back again; repeating the R34’s flight and proving once again the feasibility of such a transatlantic service. Below are pictures of the R100:

Below the lounge on the R100:

The Grand Staircase in the R100:

Unfortunately, with the crash and subsequent fire which destroyed the R101 on 5 October 1930, the R100 was grounded and then scrapped the following year. The British were no longer interested in rigid airships.

This left but three rigid airships flying: the German-built USS Los Angeles, the newly launched USS Akron, built by Goodyear-Zeppelin for the US Navy, and the Zeppelin Company’s LZ-127, Graf Zeppelin.

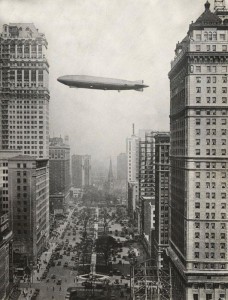

The USS Los Angeles was the US Navy’s most successful airship. She was a sturdy vessel, logging 4398 hours of flight time and flying 172,400 nautical miles (319,300 km) with no major incidents. She was a testimony to the superior engineering and craftsmanship of the Zeppelin Company. She was decommissioned in 1932, returned to service briefly after the crash of the USS Akron in 1933, and then once again mothballed. She was scrapped in 1940.

The USS Los Angeles over Washington Blvd in Detroit, 1926:

The greatest airship of all was the LZ-127 Graf Zeppelin. She was an experimental ship. To avoid valving off lift gas to compensate for fuel usage, the Graf’s engines burned Blau gas, which weighed about the same as air. This successfully innovative feature was not duplicated in any other airship.

The Graf was small compared to the R100 and R101. She only had room for 20 passengers. And while accommodations were pleasant, they were not sumptuous.

The Graf Zeppelin:

The combination lounge/dining room on the Graf:

A cabin on the Graf:

The Graf Zeppelin‘s career from 1928 to 1932 primarily involved experimental and demonstration flights displaying the airship’s capabilities. These flights included a round trip across the Atlantic in 1928, the round the world flight in 1929, the Europe-Pan American flight of 1930 (Germany to South America to North America and back to Germany), the 1931 polar expedition, two round trips to the Middle East, and a variety of other European flights.

The round the world flight set a world record. The Graf completed the circumnavigation in 21 days and could have made an even faster flight, except part of the purpose was a goodwill tour which involved spending extra time in Japan.

You can read more about her polar flight at airships.net.

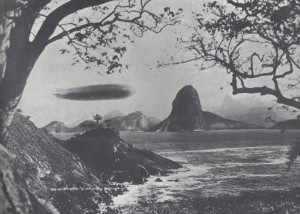

Beginning in 1932 until she was retired in 1937 after the Hindenburg tragedy, the Graf provided regular passenger, mail, and freight service between Germany and Brazil. Below is my favorite picture of the Graf Zeppelin coming flying into Rio de Janeiro.

The Graf Zeppelin was the first aircraft to fly over 1,000,000 miles (1,056,000). She made 590 flights, 144 transoceanic crossings, carried 13,110 passengers, and logged 17,177 hours of flying time. She did this without a single injury to passenger or crew. Keep in mind, her lift gas was hydrogen. Which I think proves beyond a shadow of a doubt, with the proper precautions, hydrogen is safe. She was scrapped in 1940.

The Hindenburg is well known and I won’t cover her story here. Her sister ship, the LZ-130 Graf Zeppelin (II) took her first flight on 14 September 1938. Like the Hindenburg, she was designed to fly using helium as her lift gas. However, the US government reneged on its promise to deliver helium to the Germans and the Graf Zeppelin II was inflated with hydrogen. She never entered commercial service and made but 30 flights. On 20 August 1939 she made her last flight. When she landed at 9:38 PM, the era of rigid airship flight came to an end.

The LZ-130 Graf Zeppelin (II):

More pictures of the LZ-130 can be seen at blimp info.

The rigid airships were the largest aircraft to fly. The success of the R33 and R34, the Graf Zeppelin, the USS Los Angeles, and the R100 excited the depression beleaguered public that good things were coming. Science and technology would make life better.

Lester Dent’s Zeppelin Tales and the fictional Doc Savage’s use of an airship were exciting fantasies reflective of this new hope that better times were coming.

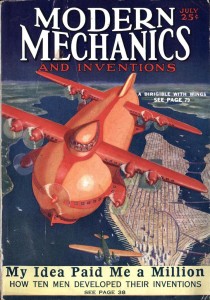

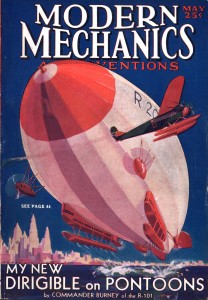

The May 1930 issue of Modern Mechanics featured an airship with pontoons (to help cut hangar costs) and the July 1929 issue of Modern Mechanix, featuring an airship with wings and boat hull (to combine the best features of airships and seaplanes), were further examples of the possibilities that airships provided to improve intercontinental transportation.

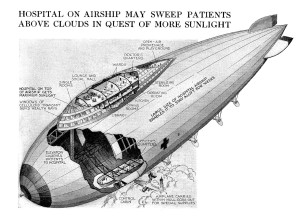

There were even thoughts of an airship tuberculosis hospital. See airships.net for the article.

The airship has and continues to excite our imaginations as no other flying machine. Is it any wonder our retro-futurist fiction continues to make our dreams reality, even if only within the realities of our imaginations.

Share This!

Enjoyed this series of aarticles a lot. I always feel a bit sed when I come to the end of the articles and read these queens of the sky where just taken down and never flew again. Maybe someone, someday…

There will be more on other aspects of flight and other things we take for granted that had their beginning in the Machine Age. So stay tuned. 🙂

Good article, CW!

I too, like that old photo of the Graf Zeppelin coming flying into Rio de Janeiro. I’m curious, though, as to when the photo was taken? In the article, you mention the flight between 1932-37 and yet I don’t see the statue of Christ the Redeemer atop mount Corcovado (if that is, in fact, Corcovado in the background). Can you confirm or should I send this off to Mulder asap?

It makes you wonder what would have happened had neither WWI nor WWII taken place? Was it the spectre of war that led to the advances that peace would never have touched upon until much later? It often seems that war, disaster, and destruction motivate our advances in such a way that we rush into our future blindly. Is this, perhaps, the reason why we fail at creating the future so often ‘predicted’ in books and film?

Writers of this genre (of which I am not) have a great ‘what if’ chance to ‘play out’ alternative histories and weave them into some wonderful tales.

Not only are these articles informative, but they are laced with ideas for the creative of mind. Great stuff.

Oh, btw, I’ve noticed a broken image. It’s this one: Dining-Room-of-LZ130.tiff

It could be that your website doesn’t like handling Tiff files or that it should be JPG instead. Just thought I’d point it out (I imagine your Spam filter is already aiming at this comment as I write…)

Thanks, Crispian!

In the pic, the Graf is entering Guanabara Bay and I believe that is Sugarloaf Mountain in the background. Christ the Redeemer on Corcovado is out of the picture. My guess is the statue is to the right. I don’t know when the picture was taken. I’m guessing after 1931, but that is just a guess.

For the Lady Dru series, which occurs in the early ’50s, World War II not having taken place, I’ve done a lot of extrapolating as to how things would have been. Of course it is all a guess, but I agree: war seems to rush us into paths that in peace time we may not have taken.

I think the great rigid airships were on their way out before the Hindenburg tragedy. They were expensive to build and operate and were slow compared to airplanes. Their only advantage was distance flying. That disappeared when Boeing, in 1939, brought out the 314 Clipper which could fly across the Atlantic. And in style. Although, still not equal to the Hindenburg. But darn close. The Graf Zeppelin II was obsolete before she took her first flight — even if she’d been inflated with helium. Sad to think those noisy vibrating piston airplanes were preferred over the quiet serenity of floating with the clouds. But we’re in a rush to get to often where we know not.

The tiff wouldn’t work, so I replaced it with a link to the “blimp info” site. I don’t see a link to the tiff in the blog, which I deleted. How did you find it? Was Mulder helping you? 🙂

This was an informative and fun series of blog posts. The Modern Mechanic covers are great. I can’t help think about what it would be like to see on flying especially through the city with skyscrapers.

Thanks Alice! Yes, those covers are great! I think it exciting to see a blimp. What would it be like to see something four times as big?