If you do a web search for “cozy catastrophe” you will come across quite a few websites parroting the nonsense that this form of the post-apocalyptic tale was written almost exclusively by white middle-class British blokes after World War II longing for the days of Empire and Tory government and that the cozy was simply their way of lashing out at the world they didn’t like.

Such a position simply reveals the ignorance of those making it. If one looks at the history of the form, one is quickly disabused of such a notion.

Of course the negative attitude of these critics has one source and that source is Brian Aldiss. Why Aldiss was seemingly so opposed to the fiction of John Wyndham baffles me and I will not attempt to understand what is probably not understandable.

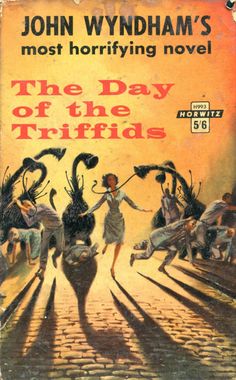

Today we will take a look at The Day of the Triffids, the 1951 novel by Wyndham which is ultimately responsible for the term “cozy catastrophe”.

Below is the BBC’s version of the Triffid

The Day of the Triffids begins with a worldwide catastrophe that’s made most everyone blind. As if that isn’t bad enough, the blindness is followed by a fast killing plague. And then there are the Triffids: those giant, mobile, carnivorous, and seemingly intelligent plants created in a lab to be a supply of an exceedingly nutritious oil.

The hero, who was recuperating in the hospital from a triffid sting and had his eyes bandaged, wakes in the morning following a beautiful meteor shower to find nothing as it should be. Eventually he removes his bandages. He can see and discovers no one in the hospital can. Workers, doctors, and patients alike. Then he discovers everyone who saw the meteors has gone blind.

At first, only the hero, Bill Masen, realizes the danger posed by the triffids and no one will listen to him. No one except for Josella Playton, whose home is overrun by triffids early on.

The triffids are manmade. Masen also speculates the meteor shower was a manmade disaster. A weapons system of orbiting satellites that accidentally went off. Masen also speculates that the plague which soon breaks out is also a biological weapon created in a lab that somehow got free.

In 1951, the horror of World War II was only six years gone. The Korean War had started the previous year, the Cold War was being waged between Russia and the West, and the threat of a nuclear war occurring was a very real fear. I remember getting civil defense pamphlets in school. People stockpiled water and food and built bomb shelters. Heinlein’s Farnham’s Freehold is a time travel story about nuclear war and the salvation one man’s bomb shelter provides.

That everyone might be wiped out was something we all felt who were alive back then, if not consciously, certainly unconsciously.

At the same time, we all hoped for a better world. A world free from war and the threat of annihilation. Is it any wonder why the cozy catastrophe, with its message of hope, was so popular? And continues to be?

The Day of the Triffids posits two types of manmade disasters: biological warfare and plant modification gone awry. The latter reminds me of the current debate over GMOs. Wyndham was clearly warning us that our end may not come in a mushroom cloud, but may be due to the fact we need to eat and growing enough food for the world is a constant problem.

The storyline is very broadly typical of the cozy. A small group of survivors bands together and tries to continue some form of civilization. Of course each group of survivors has their own spin on what the new civilization will look like.

Seemingly the main criticism of cozies is that everyone’s middle class. In Triffids, certainly Bill and Josella are. But that isn’t necessarily the case regarding the other survivors we meet. The character Coker certainly appears to be from laboring class. Regardless, though, of whatever class people start out as, everyone, in order to survive, must become a laborer.

The catastrophe has made everyone equal. In fact, when some form of militaristic authoritarian government eventually reaches Bill and Josella, They flee. They want no part of the class structure to be imposed on them.

Ultimately The Day of the Triffids is about hope in the face of adversity, about an innate sense of goodness and decency which will rise up in the face of extreme suffering and calamity, freedom from authoritarianism, and about our dreams for better future.

Looking at the novel sixty-five years after it was published, I’d say it has much in common with Heinlein’s libertarian manifesto The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. Triffids has none of the negative features pejoratively assigned to it by Aldiss and his ilk. In fact, I’d say it is the opposite. The book is about liberty, equality, and fraternity. It is a book showing that in the worst of times we can be at our best as human beings.

Comments are always welcome! Until next time, happy reading!

Share This!

I’ve never read this book, though I think about doing it every now and then. It sounds like a very odd one, which is why I havent’t picked it up yet… but maybe it’s just me 😉

It’s a good story. Very sci-fi with some political and ecological statements in it. And a little romance. Now who can’t like that? 🙂

Great post, CW!

As an aside, it appears your diligent Spam filter has securely bolted the doors and point-blank refuses to allow comments on your older posts. My simple enquiry was met with a raucous round of raspberry-blowing by the aforementioned Spam filter, clearly dismayed that its old nemesis has arisen from the depths to blemish these pages once more.

Anyway, as I was about to say, this post reminded me of when I was in primary school in England. Our teacher was explaining about the 4-minute warning and how it was likely everything would go up in smoke. We had to write a list of things that we would take into the shelter with us. I put ‘Treasure Island’ down and a dog-eared, ex-library copy of Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’ (that I had not read, but loved the cover).

The shelter was actually a wire mesh and paper mâché creation, built in the middle of the classroom. The shelter was only large enough for us to comfortably house five of us. The class was made up of twelve. We would have to decide who came in and who stayed outside. To make take things further and make it ‘interesting’, the teacher created a point system based upon our classwork and behaviour. We could get extra points if we provided information to the teacher on our fellow classmates behaviour outside of the classroom.

Needless to say, there were some complaints made by parents when it became clear as to why some children were having nightmares about the end of the world.

Personally, I still regard Golding’s ‘Lord of the Flies’ as coming closest to how we, as humans, would likely handle an apocalyptic future. There is a reason we were ‘cast out’ from the kingdom of animals – you only have to look at the disappointment in their eyes to know.

I’ve always liked Wyndham’s novel and, as you quite rightly say, it is indeed a novel about hope and the potential for humans to rise up for the better rather than revert to the more ‘feral’ existence we see expressed in literature and film more and more these days. Perhaps there is hope. Perhaps.

How very good to see your comment, Crispian. Your insights are always welcome.

All I can say is what teachers used to be able to get away with makes me shudder! Now the pendulum has swung the other way and it’s what the kids can get away with that makes me shudder. I have to say, though, that was an ingenious method of class control on the teacher’s part. Nothing works like fear and tattletaling. Stalin would have been proud!

I agree: “Lord of the Flies” is probably how things would turn out. I love your sentence on us being cast out of the kingdom of animals — sheer poetry.

There’s so much dystopian fiction today it is rather nice to read something that takes the opposite position — that we are at base people of goodwill.

On the spam filter, I had to turn off allowing comments on older posts as the spammers were having a field day. Spammers. Lord of the flies on the internet.